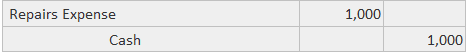

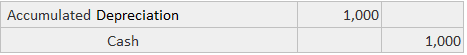

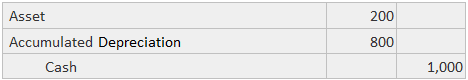

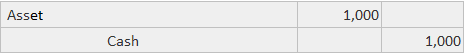

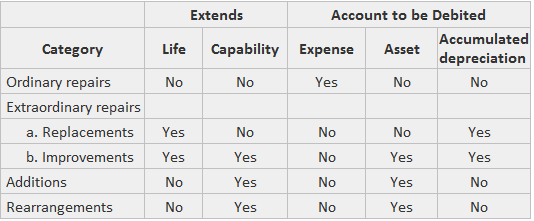

Most operating assets require expenditures for repairs, maintenance, or improvements. These subsequent costs can pose accounting problems if they are material in amount or significantly affect the asset's service life. In general terms, an accountant must choose between capitalizing the expenditure by increasing the asset's book value or expensing it in the year in which it occurs. Conceptually, the best treatment would call for capitalization of all expenditures that yield benefits beyond the end of the fiscal year. However, the practical problems of implementing this policy often preclude its use. The most obvious problem is the lack of objective criteria for determining whether and how long the benefit will last into the future. To deal with these problems, where their impact is material, it is common in general practice to use the following four classes of expenditures: Importantly, there are no clear dividing lines between these classifications. General practice has developed some common treatments of these classes of expenditures. They involve either expensing or capitalizing the expenditures. Expense: The amount spent reduces the present period's income only, and it is typically applied to ordinary repairs. For example: Capitalize: The asset's book value is increased by the amount of the expenditure, which reduces income in future periods through its effect on depreciation expense. This can be achieved using one of the following approaches: 1. Accumulated depreciation: The amount spent is taken directly out of accumulated depreciation. This is typically applied to replacements. For example: 2. Asset and accumulated depreciation: The amount spent is divided between the asset account and accumulated depreciation. This is typically applied to improvements. Also, the size of the debit to accumulated depreciation is the amount charged in prior periods on the removed component. An example is shown below. 3. Asset (gross): The amount spent is added to the asset account. This is typically applied to additions and rearrangements. For example: These rules are not uniformly followed. Furthermore, they have never been addressed in the guidelines or pronouncements of any official body or agency. However, there are few cases of abuse due to the fact that the amounts involved are often immaterial. A summary of the categories of expenditures, their effects, and their typical treatment is given below.

Example

Costs Subsequent to Acquisition FAQs

The costs subsequent to acquisition are expenditures made to acquire an asset. These include the purchase price, incidental expenses, and installation charges.

Each expenditure must be reviewed individually to determine whether it requires capitalization or immediate expensing. Many small expenditures may not require capitalization; larger ones usually do.

Ordinary repairs (decreasing the asset’s useful life or capability, but not extending it), costs of consumables used in operations (e.g., electricity and fuel in manufacturing plants), and certain other costs (e.g., training costs to make employees more effective) are expensed as incurred.

Replacements (increasing the asset’s useful life but not its capability), improvements (increasing both the asset’s useful life and capability), and certain other costs (e.g., training costs to extend capabilities of current employees) are almost always capitalized.

If the acquired asset has lost any of its capability or useful life in its condition at acquisition, it is replaced. If not, it is improved. This determination requires comparing the original with the current state of the asset in all relevant aspects (e.g., state of repair, working order and alterations or modifications that might affect its performance).

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.